Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO) A Survey

Kurt Pan

March 4, 2025

Abstract

Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO) has emerged as a transformative concept in cryptography, aiming to make computer programs unintelligible while preserving their functionality. This survey provides an in-depth review of iOs evolution, theoretical foundations, and farreaching applications, structured in the style of an academic paper. We begin by motivating iO in the context of classical program obfuscation and summarizing its significance as a cryptographic master tool. We then present formal definitions and preliminaries needed to rigorously understand iO. The survey examines the core theoretical underpinnings of iO, including major candidate constructions and the complexity assumptions they rely on. We also explore the remarkable applications enabled by iO from constructing fundamental cryptographic primitives under minimal assumptions to advanced protocols previously deemed out of reach. Recent research milestones are discussed, highlighting state-of-the-art iO constructions based on well-founded hardness assumptions and the implications for cryptographic theory. Finally, we outline open problems and future directions, such as improving efficiency, simplifying assumptions, and addressing lingering challenges. Through comprehensive coverage of both theory and practice, this survey underscores iOs central role in modern cryptographic research and its potential to unify a wide range of cryptographic goals.

Contents

2 Preliminaries 6 2.1 Program Obfuscation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 2.2 Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO) . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.3 Basic Hardness Assumptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 3 Theoretical Foundations of iO ..... 8 3.1 Initial iO Constructions (2013-2014) ..... 9 3.2 Punctured Programming Technique ..... 10 3.3 iO and Functional Encryption – Equivalence ..... 12 3.4 Progress in Assumptions (2015-2019) ..... 12 3.5 Limitations and Impossibility Results ..... 14 3.6 Summary of Theoretical Status ..... 14 4 Applications of iO ..... 14 5 Current State of Research ..... 19 5.1 Confidence in iOs Existence ..... 19 5.2 Efficiency and Complexity Concerns ..... 21 5.3 Ongoing Research Directions ..... 21 6 Open Problems and Future Directions ..... 23 7 Conclusion ..... 27

1 Introduction

Program obfuscation is the process of converting a computer program into a form that is functionally equivalent to the original but difficult for humans or algorithms to understand. A virtual black-box (VBB) obfuscator was long considered the ideal: an obfuscated program would reveal nothing beyond what is observable from input-output behavior (as if one only had black-box access to the function). However, a seminal result by \(\left[\mathrm{BGI}^{+} 01\right]\) demonstrated that general-purpose VBB obfuscation is impossible for arbitrary programs. They constructed (under a mild assumption that one-way functions exist) a family of functions for which no efficient obfuscator can hide certain hidden properties of the program . This impossibility result dashed hopes of perfect obfuscation and prompted researchers to seek weaker definitions that might still be achievable.

Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO) was proposed as a viable relaxation of VBB obfuscation. Informally, iO requires that given any two equivalent programs (or circuits) that compute the exact same function, their obfuscations should be computationally indistinguishable \(\left[\mathrm{GGH}^{+} 13\right]\). In other words, if two programs produce identical outputs for all inputs, then an observer should not be able to tell which obfuscated program corresponds to which original program. Unlike VBB, iO does not guarantee that all information about a single program is hidden, it only guarantees that nothing can be learned that differentiates one implementation from another equivalent implementation [Edw21]. This subtle weakening avoids the [BGI \(\left.{ }^{+} 01\right]\) impossibility, making iO a theoretically achievable goal. Initially, the utility of this strange new notion was unclear; iO does not by itself hide secrets in a single program, but rather provides a form of relative security between functionally identical programs.

The cryptographic communitys interest in iO surged after a breakthrough in 2013. [GGH \({ }^{+}\)13] (FOCS 2013) presented the first candidate construction for indistinguishability obfuscation. Their work provided a concrete (albeit heuristic) approach to realize iO for all polynomialsize circuits, using novel tools called multilinear maps [GGH12] to encode the program. This result was a watershed moment : it suggested that iO might actually exist in the real world, contrary to earlier skepticism. Almost immediately, researchers uncovered a staggering range of applications for iO [BV15] (FOCS 2015). It became apparent that iO is a powerful generalized cryptographic primitive: in the words of Bitansky and Vaikuntanathan, iO is “powerful enough to give rise to almost any known cryptographic object”. Indeed, subsequent works [SW14] showed that if one assumes iO (together with standard hardness assumptions like one-way functions), one can construct an expansive array of cryptographic schemes that were previously unknown or only conjectured to exist. [SW14] (STOC 2014) demonstrated how to use iO to realize advanced cryptographic goals, settling open problems that had stood for years . In [SW14], they introduced the punctured programming technique and used iO to solve the long-standing problem of deniable encryption – an encryption scheme where a sender can produce a fake decryption key that makes a ciphertext appear as an encryption of a different message. The same work posited iO as a “central hub” for cryptography, showing that many disparate cryptographic primitives could be constructed through the lens of iO . The floodgates opened: countless cryptographic constructions (from standard public-key encryption to “first-of-their-kind” primitives) were realized by leveraging iO's unique capabilities. This explosion of results cemented iO's reputation as a “holy grail” of cryptography – a single primitive that, if achieved in full generality, would enable or simplify the construction of nearly everything else [BV15].

Despite this promise, early iO candidates were based on complex new assumptions and remained unproven. Over the next several years, a cat-and-mouse game ensued between proposal and cryptanalysis \({ }^{1}\). The initial constructions relied on heuristic objects (multilinear maps) that were not firmly grounded in well-studied hardness assumptions, leading to attacks and broken schemes. This period of “emotional whiplash” saw cryptographers alternate between optimism and doubt regarding iO's existence . Nevertheless, the community's understand-

[^0]ing deepened with each iterated construction and break [Edw21]. Major advances have been achieved in the last few years: in 2020, researchers unveiled the first iO constructions based on standard (or wellfounded) assumptions [JLS20], markedly increasing confidence that iO can be realized without uncontrolled heuristics . At the same time, these newer solutions highlight remaining challenges such as efficiency and the desire for even simpler assumptions.

This survey provides a comprehensive review of indistinguishability obfuscation, targeting researchers and advanced practitioners. We cover both the theoretical foundations of iO and its diverse applications. In section 2, we give formal definitions and necessary cryptographic background. In section 3 , we delve into iO constructions, from the original frameworks (based on multilinear maps and functional encryption) to the latest “standard assumption” breakthroughs. In section 4, we explore how iO has revolutionized the landscape of cryptographic primitives and protocols, enabling solutions like functional encryption for all circuits, secure multi-party computation improvements, and more. Section 5 surveys the state-of-the-art, summarizing known constructions, the assumptions underpinning them, and their current security status. In section 6 , we discuss the many open challenges that remain on the road to practical, provably secure iO including efficiency barriers, reducing assumptions, and understanding the limits of iO's power. We conclude with reflections on the significance of iO and its future role in cryptography.

Impossibility & Definitiهrirst Constructions & Applications Standard Assumptions Figure 1: Timeline of significant developments in indistinguishability obfuscation research.

2 Preliminaries

This section introduces the formal definition of indistinguishability obfuscation and related concepts needed to understand iOs foundations. We assume familiarity with basic cryptographic notions such as polynomial-time adversaries, negligible functions, and standard hardness assumptions (e.g., one-way functions).

2.1 Program Obfuscation

We model programs as Boolean circuits for simplicity. An obfuscator \(O\) is a probabilistic polynomial-time \(\mathrm{PPT)}\) algorithm that takes a circuit \(C\) as input and outputs a new circuit \(C^{\prime}=\) $O©\(, intended to be a “scrambled” version of \)C$ that preserves \(C\) 's functionality.

The soundness requirement is that \(C^{\prime}\) computes the same function as \(C\) for all inputs (perhaps with overwhelming probability if \(O\) uses randomness).

Informally, security requires that \(C^{\prime}\) reveals as little as possible about the internal details of \(C\).

Different obfuscation definitions formalize “as little as possible” in various ways.

The strongest traditional definition is virtual black-box (VBB) obfuscation, which demands that anything one can efficiently compute from the obfuscated circuit \(C^{\prime}\) could also be computed with only oracle access to \(C\) (i.e. by treating \(C\) as a black-box function evaluator).

Definition 2.1 (circuit obfuscator). A probabilistic algorithm \(\mathcal{O}\) is a (circuit) obfuscator if the following three conditions hold:

- (functionality) For every circuit \(C\), the string \(\mathcal{O}©\) describes a circuit that computes the same function as \(C\).

- (polynomial slowdown) There is a polynomial \(p\) such that for every circuit \(C,|\mathcal{O}©| \leq p(|C|)\).

- (“virtual black box” property) For any PPT A, there is a PPT S and a negligible function \(\alpha\) such that for all circuits \(C\)

$$ \left|\operatorname{Pr}[A(\mathcal{O}©)=1]-\operatorname{Pr}\left[S^{C}\left(1^{|C|}\right)=1\right]\right| \leq \alpha(|C|) $$

We say that \(\mathcal{O}\) is efficient if it runs in polynomial time. [BGI \(\left.{ }^{+} 01\right]\) showed that a general VBB obfuscator for all circuits cannot exist.

They constructed a family of circuits \(\left{C{k}\right}\) (dependent on a one-way function) such that there exists a secret property \(\pi\left(C{k}\right)\) that is easy to learn from the circuit description yet provably hard to determine with only oracle access to the underlying function.

This result implies any would-be obfuscator \(O\) that works on all circuits must fail (leak \(\pi\left(C_{k}\right)\) ) on some circuit in the family.

Intuitively, the impossibility stems from the obfuscators requirement to hide every aspect of the computation; the contrived circuits of [ \(\left.\mathrm{BGI}^{+} 01\right]\) have an implanted secret that any correct program reveals by definition (since the program itself can be examined), but which cannot be extracted via black-box queries alone.

2.2 Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO)

The iO definition relaxes the VBB guarantee. An obfuscator \(O\) is indistinguishability obfuscating if for any two circuits \(C{0}\) and \(C{1}\) of the same size that compute identical functions (i.e \(C{0}(x)=C{1}(x)\) for all inputs \(x\) ), the distributions \(O\left(C{0}\right)\) and \(O\left(C{1}\right)\) are computationally indistinguishable. In other words, if an adversary is given an obfuscation of one of two equivalent circuits (chosen at random), they cannot tell which one was obfuscated. This must hold for all equivalent circuit pairs and for all polynomial-time distinguishers. By design, iO only provides a meaningful guarantee when two different circuits compute the same function. If \(C{0}\) and \(C{1}\) differ in functionality, iO places no restrictions indeed, one can trivially distinguish \(O\left(C{0}\right)\) vs \(O\left(C{1}\right)\) by just running them on some input where their outputs differ. Thus, iO does not hide specific information within a single program in the absolute sense; it ensures that whatever one program reveals, any other equivalent program would reveal as well. Any implementation-dependent secrets are safe only to the extent that there is no alternate implementation to compare against.

Formally, for security parameter \(\lambda\), and any two functionally equivalent circuits \(C{0}, C{1}\) with \(\left|C{0}\right|=\left|C{1}\right|\), we require:

$$ \operatorname{Dist}\left(O\left(1, \lambda, C{0}\right) ; O\left(1, \lambda, C{1}\right)\right) \leq \operatorname{negl}(\lambda) $$

where \(\operatorname{Dist} X ; Y\) denotes the maximum advantage of any PPT distinguisher in distinguishing distribution \(X\) from \(Y\), and \(\operatorname{negl}(\lambda)\) is a negligible function. The obfuscator is also required to have a polynomial slowdown: there is a polynomial \(p(\cdot)\) such that for any circuit \(C\) of size \(n\), the obfuscated circuit \(C=O©\) has size at most \(p(n)\).

This definition, first put forth explicitly by Garg et al. (2013) , evades the Barak et al. impossibility because it does not demand security for a single given circuit in isolation. If \(C\) has some secret property that is efficiently extractable from its description, iO does not prevent that from being learned iO only guarantees that another equivalent circuit \(C\) would leak the same property. In the pathological case from Barak et al.s result, no alternate equivalent circuit exists that hides the secret property (the obfuscation cannot eliminate the secret without changing functionality), so iO does not promise security there. In practice, however, cryptographers leverage iO by carefully designing equivalent programs that do conceal secrets unless one knows a specific trapdoor. The indistinguishability property then ensures an adversary cannot tell whether they have the real program or a secret-hiding equivalent version, which can be enough to guarantee security in applications. This style of proof underpins many iO-based constructions.

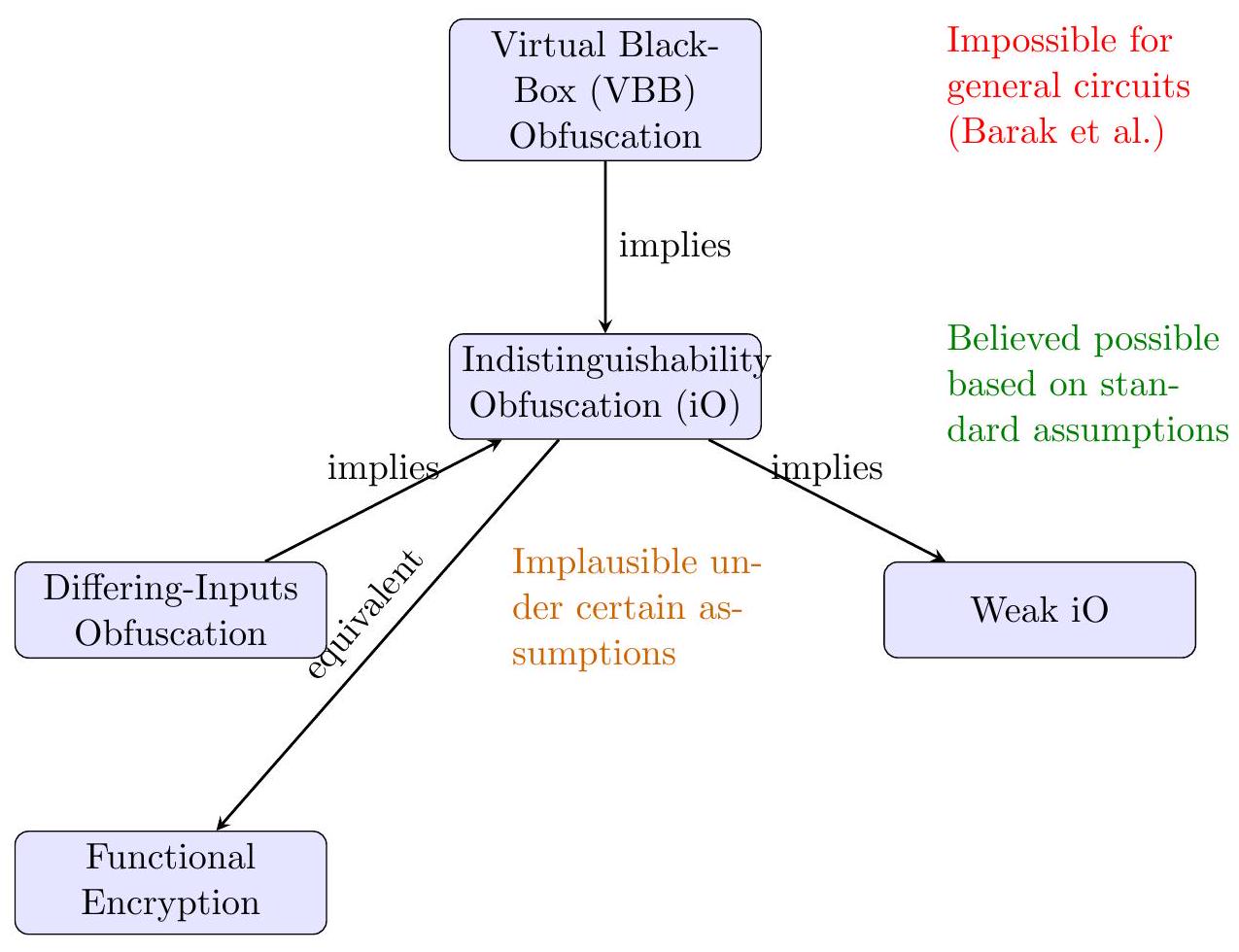

Relationship to Other Notions Indistinguishability obfuscation is considered the weakest useful form of general obfuscation any stronger notion (like VBB) would imply iO , but iO itself is potentially easier to realize. There are also intermediate notions studied, such as credible or differing-inputs obfuscation, which impose security only for circuits that are equivalent on most inputs or under certain distributions. These are beyond our scope, though we note that many positive results use iO as a stepping stone or assume slightly stronger variants when needed for proof convenience. Importantly, iO in combination with other standard primitives often yields security equivalent to (or at least as good as) VBB obfuscation for the overall scheme. As well see in applications, even though iO by itself is a weak guarantee, it becomes extremely powerful when used cleverly in cryptographic protocol design.

2.3 Basic Hardness Assumptions

Since general obfuscation was proven impossible in an informationtheoretic sense, any realization of iO must rely on computational hardness assumptions. Early iO candidates leaned on new algebraic assumptions (related to multilinear maps) which we will describe later. Modern iO constructions rely on a constellation of assumptions such as the hardness of learning with errors (LWE), certain elliptic-curve group assumptions, and coding theory problems. We will introduce these assumptions informally in context. For now, it suffices to say that iO cannot exist in a vacuum like most cryptographic primitives, it is achievable if and only if certain problems are computationally infeasible to solve for an attacker. Part of the challenge in iO research is identifying the minimal and most believable set of such assumptions needed to securely instantiate an obfuscator.

3 Theoretical Foundations of iO

Indistinguishability obfuscations theoretical development has been driven by a sequence of landmark results that gradually brought the concept

from theory to (approximate) reality. In this section, we survey the major iO constructions and the ideas behind them, as well as the evolving assumptions that underpin these constructions.

Figure 2: Hierarchy of program obfuscation notions and their feasibility.

3.1 Initial iO Constructions (2013-2014)

The first candidate construction of iO for general circuits was given by Garg, Gentry, Halevi, Raykova, Sahai, and Waters (GGHRSW) in 2013 . This breakthrough work provided a blueprint for how iO could be built in principle. The construction was accomplished in three main steps : iO for NC1 via Multilinear Maps: They described a candidate obfuscator for circuits in the class \(\mathrm{NC}^{1}\) (circuits of logarithmic depth). Security of this obfuscator was based on a new algebraic hardness assumption introduced in the paper, using a primitive called a multilinear jigsaw puzzle essentially a form of multilinear map. Multilinear maps (proposed shortly prior by Garg, Gentry and Halevi ) are a generalization of the DiffieHellman bilinear pairing concept to allow multi-party exponentiation. In simple terms, a multilinear map lets one encode secret values in such a way that certain polynomial relations can be checked publicly (like an \(n\)-way DiffieHellman key), but recovering any hidden component is as hard as solving a hard math problem (originally, related to lattice problems ). GGHRSWs NC1 obfuscator used these algebraic structures to create a garbled encoding of a circuits truth table that an evaluator can still execute. The novel multilinear jigsaw puzzle assumption in their work was needed to argue that the obfuscation leaks no more than intended . Bootstrapping to All Circuits: Next, they showed how to obfuscate any general circuit \(C\) by recursively leveraging the NC1 obfuscator. The trick was to use Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) as a bridge . They obfuscated an NC1 circuit that included the decryption algorithm for FHE, thereby creating a system where an arbitrary circuit \(C\) could be pre-encrypted and evaluated within the obfuscated NC1 decoder. In effect, this bootstrapping used FHE to compress the task of evaluating \(C\) into an \(\mathrm{NC}^{1}\) procedure (decrypt-and-evaluate) which iO could handle. The result was an indistinguishability obfuscator for all polynomial-size circuits, assuming the security of the \(\mathrm{NC1} \mathrm{iO} \mathrm{scheme} \mathrm{and} \mathrm{the} \mathrm{underlying} \mathrm{FHE}\).

The GGHRSW construction demonstrated feasibility: iO could exist if these new hardness assumptions (e.g., the multilinear map jigsaw puzzle assumption) held true. It is worth noting, however, that the security was not proved from established assumptions; rather, the paper introduced entirely new algebraic problems on lattices that had not been vetted by years of cryptanalysis. This left a question mark on how much confidence to place in the candidate. Nonetheless, the conceptual contributions especially the idea of combining a limited obfuscator with FHE to get general obfuscation have influenced all later developments.

3.2 Punctured Programming Technique

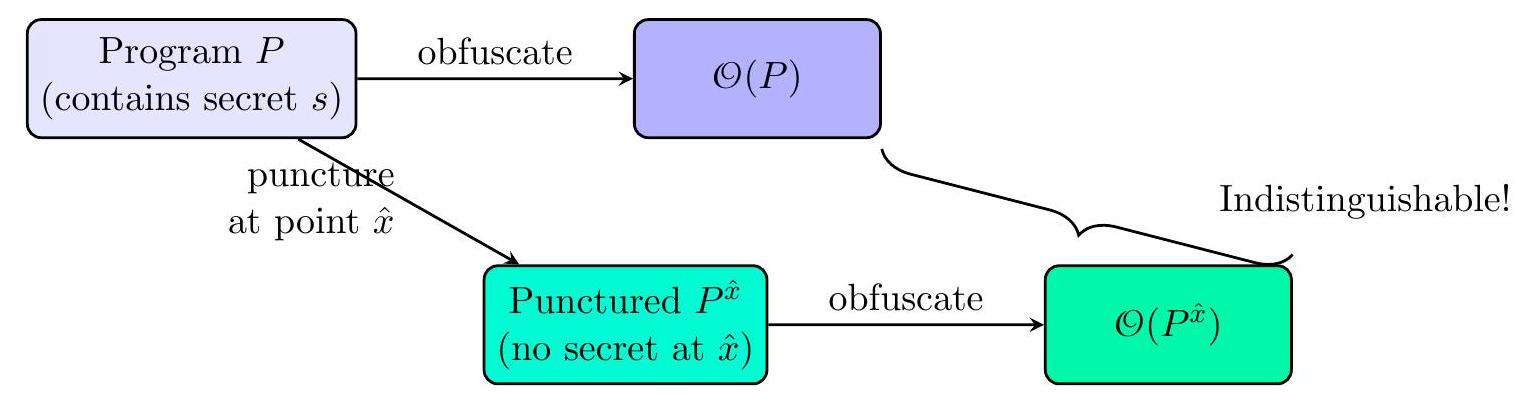

In parallel with constructing iO itself, researchers needed new techniques to use iO in applications (since standard proof techniques often treat cryptographic primitives in a black-box way, which iO inherently is not). A key idea introduced by Sahai and Waters (STOC 2014) is punctured programming .

The intuition is as follows: suppose you have a secret key or secret value \(s\) you want to hide in a program, but you can afford for the program to not use \(s\) on one specific input (to punt on that input). You can create two versions of the program: one full program \(P\) that uses \(s\) normally, and one punctured program \(P^{\hat{x}}\) that has \(s\) removed or scrambled in the code path for some particular input \(\hat{x}\). Both programs are functionally identical for all inputs except \(\hat{x}\) (where \(P^{\hat{x}}\) might output some dummy value instead of using \(s\) ). If chosen carefully \(\hat{x}\) can be a point that an adversary would need to query to learn the secret. Now,

Both programs behave identically except possibly at input \(\hat{x}\)

Secret s is removed from the code path for input \(\hat{x}\)

Figure 3: Visualization of the punctured programming technique used in iO applications. iO guarantees that an adversary cannot distinguish whether they have \(O(P)\) or \(O\left(P^{\hat{x}}\right)\). If we can show that in either case the adversary cannot actually obtain the secret \(s\) (in one case because \(s\) isnt even there, in the other because even if its there, extracting it would solve some hard problem), then \(s\) is secure. This technique cleverly sidesteps the fact that iO doesnt hide secrets outright instead, it leverages indistinguishability to play a game between a real program and a tampered (punctured) program to argue security.

Punctured programming is often used in combination with puncturable pseudorandom functions (PRFs) . A puncturable PRF is a special PRF where one can derive a restricted key that evaluates the PRF on all inputs except one punctured point \(t\); and critically, given this punctured key, the PRFs output at the punctured point \(t\) remains pseudorandom (unknown). Using such PRFs, Sahai and Waters constructed an obfuscated program that included a PRF key \(K\), but whenever the program needed to use \(K\) on the punctured point, it would instead output a fixed value (not using \(K\) ). The punctured PRF security ensured that an adversary who sees the obfuscated program cannot distinguish it from one where the PRF outputs at that point are truly random meaning the adversary gains no information about the real PRF key. This approach was instrumental in building a public-key encryption scheme from just a one-way function and iO, among other applications . In fact, the Sahai-Waters 2014 paper showed how to achieve standard Public-Key Encryption (PKE) using only an iO obfuscator and a one-way function (OWF) a striking result because PKE generally cannot be based on OWFs alone in a blackbox world. The non-black-box use of iO (via punctured programming) bypassed that limitation.

3.3 iO and Functional Encryption – Equivalence

Following the initial iO candidate, researchers explored connections between iO and other advanced primitives. A remarkable result by Bitansky and Vaikuntanathan (FOCS 2015) showed that iO is essentially equivalent in power to public-key functional encryption . They gave a construction of iO assuming the existence of a sufficiently powerful functional encryption (FE) scheme, and conversely, prior works already indicated how to get FE from iO. In their abstract they noted that iO was powerful enough to give rise to almost any known cryptographic object, yet FE was seemingly a weaker notion; their work bridged this gap by showing FE with certain properties can actually lead to iO . The significance of this is twofold: (1) it provided an alternative conceptual path to iO (via FE) which could be useful if FE is easier to construct under standard assumptions, and (2) it helped simplify and modularize iO constructions by breaking the problem into smaller pieces (designing FE, which was better understood by then, and then upgrading it to iO ).

3.4 Progress in Assumptions (2015-2019)

One of the main theoretical questions about iO after 2013 was: Can we base iO on standard, well-established hardness assumptions? Early constructions relied on ad-hoc assumptions tied to new objects like multilinear maps. These maps (e.g. GGH13 multilinear lattices ) soon came under cryptanalytic attacks, undermining confidence. Over time, researchers proposed new candidate constructions that traded one assumption for another. For instance, some works assumed variants of the learning with errors (LWE) problem (a lattice-based assumption considered standard) but required other exotic assumptions alongside it. Others introduced assumptions like graph-induced multilinear maps, degree-preserving PRGs, or strengthening of existing ones (e.g. requiring sub-exponential hardness of DDH or LWE). The theoretical trend was a slow chipping away at the assumption barrier: reducing complex or circular assumptions to simpler, more standard ones.

A key milestone was achieved by Jain, Lin and Sahai in 2020, who constructed an iO scheme from a combination of four assumptions, each of which has a long history in cryptography or coding theory . This result was heralded as the first fully plausible iO candidate, as all its assumptions are considered plausible by most experts (albeit some in new settings). In simplified terms, their construction assumes the security of: A bilinear map assumption on elliptic curves (a variant of the Diffie-Hellman hardness used in pairing-based cryptography). The Learning With Errors (LWE) lattice problem (a cornerstone of post-quantum cryptography) in a sub-exponential security regime. A hardness assumption about decoding random linear codes (related to the well-known difficulty of error-correction decoding without a secret key) . A structured pseudorandomness assumption (instantiated via a pseudorandom generator or variant of the Goldreich PRG conjecture).

One highlight is the use of random linear codes: for decades, coding theory suggested that decoding a general random linear code (without structure) is intractable, and this was now brought in as a cryptographic assumption . Sahai noted that breaking this assumption would require a breakthrough in algorithms that has eluded researchers for \(70+\) years , lending credence to its hardness. The JainLinSahai (JLS) construction showed how to cleverly combine ingredients from disparate areas (lattices, codes, pairings) to achieve iO, reflecting a deep synthesis of cryptographic techniques.

Around the same time, other researchers achieved complementary results. A series of works by Agrawal, Wichs, Brakerski, and others aimed to base iO primarily on LWE, with only minimal extra assumptions. Notably, one construction achieved iO using LWE plus a single (relatively mild) circular security assumption . Circular security (roughly, that its safe to have encryptions of secret keys under themselves) is a heuristic assumption often made in cryptography. By reducing all other components to LWE (which is a well-studied assumption, even believed secure against quantum attacks), these works came tantalizingly close to the dream of iO from one standard assumption . Barak (2020) describes this convergence as different seasons of progress: the community has not fully reached the holy grail of basing iO on just LWE alone, but the gap has narrowed dramatically .

Its worth mentioning that virtually all current iO schemes require assumptions to hold with sub-exponential security. This means, for example, if using LWE, one must assume the attacker cannot solve the lattice problem even with \(2^{n^{\epsilon}}\) time (for some \(\epsilon>0\) ) when the dimension is \(n\). These stronger hardness requirements are often needed in the security proof to perform union bounds or to handle hybrid arguments involving exponentially many possibilities (e.g., guessing a PRF key index). While sub-exponential hardness assumptions are not uncommon in cryptographic theory, they do make assumptions strictly stronger and are a target for improvement in future research.

3.5 Limitations and Impossibility Results

Alongside positive results, researchers have also investigated what cannot be achieved with iO. Interestingly, even iO (with OWFs) is insufficient for certain tasks under black-box reductions. For instance, one result showed that there is no fully black-box construction of collisionresistant hash functions from iO and one-way permutations. In other words, iO doesnt automatically solve every cryptographic problem collision-resistant hashing seems to require additional assumptions or non-black-box techniques beyond just iO. Another work showed that iO (or even private-key functional encryption) cannot generically yield key-agreement protocols without extra assumptions. These results remind us that iO , while extremely powerful, has its limits and must be applied with care. They also encourage the exploration of non-blackbox techniques (like punctured programming) as essential in iO-based constructions, since purely black-box reductions often run into such barriers .

3.6 Summary of Theoretical Status

As of now, indistinguishability obfuscation has moved from a theoretical concept to a primitive with multiple plausible constructions. The evolution has been marked by a reduction in the speculative nature of assumptions: from entirely new hardness assumptions in 2013, we have reached a point where iO can be constructed from assumptions that are standard or at least closely related to well-studied problems (LWE, DDH on elliptic curves, etc.). Theoretical techniques like punctured programming, multilinear maps, functional encryption, and homomorphic encryption have all contributed to making iO feasible. Still, feasible in theory does not yet mean practical the schemes are extraordinarily complex and inefficient. However, the theoretical groundwork laid over the last decade provides a clear direction for further research, and it establishes iO as a central object of study in cryptography with connections to numerous other areas of theory.

4 Applications of iO

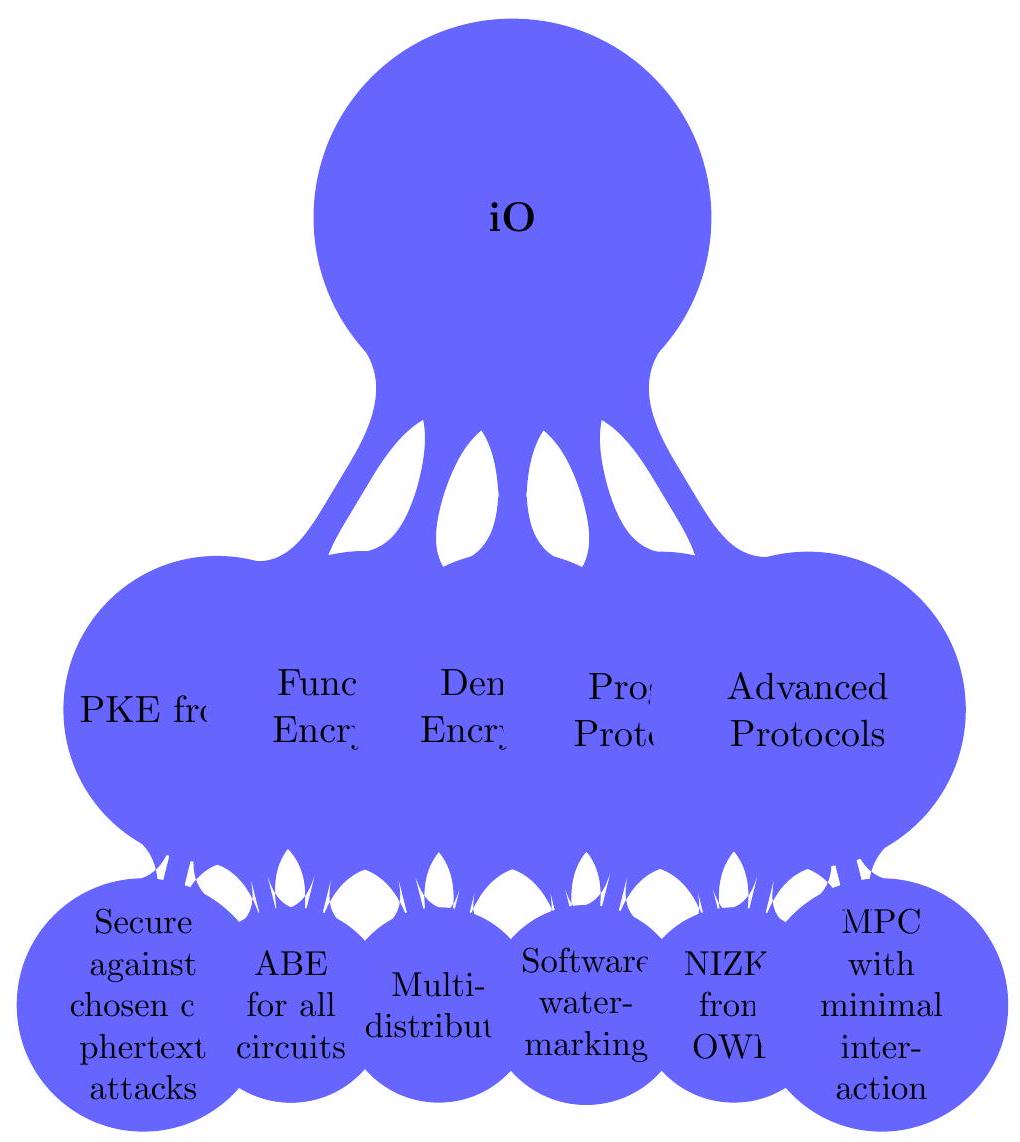

One reason iO is often dubbed a central hub or crypto-complete primitive is the astonishing breadth of applications it enables . Once re-

| Construction | Year | Key Assumptions | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGHRSW | 2013 | Multilinear maps, FHE | Broken (multilin- ear map attacks) |

| GGH15 | 2015 | Multilinear maps, graph- induced multilinear maps |

Partially broken |

| Lin-Vaikuntanathan | 2016 | LWE, PRGs with constant lo- cality |

Theoretical; un- broken |

| Lin-Pass | 2018 | Subexponential LWE, weak PRGs |

Theoretical; un- broken |

| Jain-Lin-Sahai | 2020 | LWE, bilinear maps, random linear codes, structured PRGs |

Current state-of- art; unbroken |

| Wee-Wichs | 2021 | LWE plus circular security | Simplest assump- tions; unbroken |

Table 1: Comparison of major iO construction approaches and their security status. searchers had a candidate iO in hand, they quickly discovered that many cryptographic constructions some previously known and some entirely new could be built or improved by assuming iO. We highlight several important applications and impacts of iO on cryptographic primitives and protocols.

Public-Key Encryption from Minimal Assumptions Perhaps the most celebrated application is the construction of public-key encryption (PKE) schemes from iO and only one-way functions. It is well-known that PKE cannot be achieved from one-way functions alone in a black-box manner (this is related to the separation of PKE from symmetric-key primitives in standard complexity assumptions). However, Sahai and Waters showed that by using iO, one can circumvent this limitation . In their approach, the encryption algorithm of a symmetric-key scheme (which normally uses a secret key) is obfuscated and made public. Concretely, take a one-way function \(f\) and use it to derive a pseudorandom function; then obfuscate a program that has the PRF key hardwired and, on input a message, uses the PRF output to one-time-pad encrypt the message. The obfuscation of this program becomes the public key, and the secret key is the seed to invert the oneway function (or evaluate the PRF at the punctured point). Because of indistinguishability obfuscation and punctured PRFs, an attacker cannot extract the hidden key from the obfuscated encryption program This yields a secure public-key scheme, an achievement illustrating how iO acts as a sort of alchemists stone to turn base primitives (one-way

Figure 4: Applications enabled by indistinguishability obfuscation. functions) into full-blown public-key cryptosystems. Deniable Encryption Deniable encryption (introduced by Canetti et al. in 1997) is an encryption scheme where senders (or receivers) can produce fake secrets that make a ciphertext appear to decrypt to a different message, thus denying the true message under coercion. Despite years of attempts, fully deniable encryption (in the multi-distributional sense) wasnt achieved under standard assumptions. Using iO, Sahai and Waters finally constructed the first sender-deniable encryption scheme. The idea, at a high level, was to obfuscate an encryption program that can operate in two modes depending on a hidden switch (a punctured program trick): one mode uses the real message, another uses a fake message. If coerced, the sender can provide a fake input that toggles the fake mode. The security of iO ensures an adversary cannot tell which mode the obfuscated program was actually using when producing the ciphertext, thereby providing deniability. This application not only solved a long-standing open problem, but also demonstrated how iO can serve as a substitute for the unattainable ideal obfuscation in complex security definitions.

Functional Encryption and Beyond As mentioned earlier, iO directly enabled constructing very general functional encryption (FE) schemes. With iO, one can create an FE for any circuit, which was far beyond the capabilities of pre-iO techniques (which could only handle limited function classes like inner-products or NP predicates under specific assumptions). The existence of general FE is itself extremely powerful, subsuming many other primitives like identity-based encryption, attribute-based encryption (ABE), and witness encryption. Indeed, many of these primitives were either simplified or shown to be constructible via iO. For example, iO can yield identity-based encryption by obfuscating a program that checks the identity and then decrypts with a hardwired master secret. Traditional ABE schemes that required complex pairings assumptions can alternatively be built using iO and simpler building blocks, often with much shorter ciphertexts or keys as a trade-off.

Traitor Tracing and Watermarking In the domain of digital rights management, traitor tracing schemes allow a content distributor to trace the source of a leaked decryption key (the traitor) when pirates collude to build a pirate decoder. Similarly, software watermarking allows embedding an undetectable marker in a program that can be used to prove ownership. Both of these advanced primitives saw progress through iO. For instance, Nishanth Chandran et al. and others leveraged iO to build software watermarking schemes for pseudorandom function programs, something previously not known under standard assumptions. The general approach is to obfuscate programs in such a way that the obfuscation inherently contains either a traceable mark or the ability to catch if its been modified. iO gives the ability to argue that the mark cannot be removed without fundamentally changing the programs function (which would be noticeable) an argument otherwise hard to make without an obfuscation guarantee. Traitor tracing schemes with short ciphertexts have also been built using iO by embedding tracing capabilities into obfuscated decoder programs.

Secure Multiparty Computation and Zero-Knowledge Indistinguishability obfuscation has contributed to reducing complexity in secure multiparty computation (MPC) and non-interactive proof systems. Huijia Lin notes that iO could enable extremely efficient secure multiparty communication protocols, possibly achieving security with minimal overhead. The intuition is that parties could exchange obfuscated stateful programs that encapsulate the next-step of a protocol, thereby removing the need for many rounds of interaction. Additionally, iO can be used to obtain non-interactive zero-knowledge (NIZK) proofs for NP by obfuscating a program that contains a hardcoded NP witness and only outputs a confirmation if a provided statement is true. Normally, such a program would reveal the witness if inspected, but iO ensures that if two statements are true, their corresponding proof programs (which do contain different witnesses internally) are indistinguishable to the verifier. Early works constructed NIZK from iO and one-way functions, achieving in principle what previously required heavy tools like pairings or the random oracle model.

Universal Composition and Advanced Protocols iOs applications extend to virtually any scenario where a cryptographic protocol or primitive could benefit from a party being able to compute a function without revealing how they are computing it. For example, in program obfuscations original motivation software protection iO would allow software vendors to distribute programs that hide their internal logic or secret keys, solving an important practical problem if it were efficient. While current iO is far from practical, the principle stands that it would be the ideal solution to prevent reverse-engineering of software, viruses, or even cryptographic white-box implementations (like an obfuscated DRM player that embeds a decryption key yet is hard to extract).

Another frontier is obfuscation for cryptographic protocol steps. In cryptographic protocols, we often assume parties run certain algorithms (key generation, signing, etc.) honestly. With iO, one can sometimes obfuscate a protocol algorithm and give it to other parties such that they can execute it without learning the secret within. This has been used to achieve things like delegatable pseudorandom functions and verifiable random functions by obfuscating key-holding algorithms in a way that preserves output correctness but hides the key.

In summary, indistinguishability obfuscation has proven to be an extremely versatile tool. Researchers have shown that any cryptographic system or protocol that can be realized in an ideal model (e.g., using a random oracle or a black-box access to a functionality) can often be instantiated in the real world using iO. This effectively means iO, combined with simple primitives like one-way functions, gives a way to build many cryptographic constructions that were previously conjectured but not realized. Indeed, iO has been used to achieve or simplify: one-round multiparty key exchange, time-lock puzzles with no computational assumptions (by obfuscating a loop that runs for a specific number of steps), and more. While each application may require additional assumption or clever construction, iO has lowered the barrier in a host of cryptographic problems, turning several unknown possibility results into concrete (if still theoretical) constructions.

5 Current State of Research

The rapid developments in iO research over the past few years have significantly shifted the landscape. In this section, we discuss the current state-of-the-art for indistinguishability obfuscation: what constructions are considered secure today, what assumptions they rely on, and how the communitys confidence in iO has evolved. We also address practical considerations and remaining hurdles from a research standpoint.

5.1 Confidence in iOs Existence

After the initial excitement of 20132014, the cryptographic community grew cautiously skeptical due to the series of breaks targeting candidate multilinear maps. For some time, whether general iO existed at all was an open question you might get different answers to, depending on whom you asked and which ePrint report they read that week . However, the whiplash has eased with the advent of constructions based on well-founded assumptions. The 2020 JainLinSahai result was a turning point: it showed that by assuming several standard hardness conjectures (LWE, codes, pairings, etc.), one can obtain iO . This greatly increased the communitys confidence that iO is part of our cryptographic reality (much like we believe secure multiparty computation is possible even though early protocols were inefficient). The newer candidate has so far withstood public scrutiny; no fatal flaw has been found in the underlying assumptions or the security proof, although its still relatively recent. Likewise, the parallel line of work that nearly bases iO on just LWE (plus a mild assumption) has added optimism, since LWE is a widely trusted foundation . Overall, while some healthy skepticism remains especially because the constructions are enormously complex most experts now cautiously lean towards believing iO can be instantiated in theory. This is a stark change from, say, 2015 when the prevalent attitude was uncertainty.

Assumptions and Security of Current Constructions. The state-of-the-art iO constructions, broadly speaking, fall into two categories: Multi-Assumption Constructions (e.g., JLS 2020): These use a combination of several assumptions, each moderate by itself, in unison. For instance, the JLS scheme assumes four things: sub-exponential LWE, a coding assumption, a Diffie-Hellman style assumption on groups, and a locality-based PRG assumption . Because each of these has been studied individually (to varying extents), the construction is termed heuristic-free it doesnt rely on a completely untested assumption like previous candidates did. The security proof reduces an attack on the obfuscator to breaking one of these assumptions. To date, none of these assumptions have been disproven (and indeed some, like LWE, have withstood a great deal of testing). Thus, the security of the scheme is only as questionable as the conjectures themselves. Some of the assumptions (like the linear code assumption) are new to cryptography, so they havent received decades of attention; but they are grounded in problems known to be hard in other fields (coding theory), which inspires some confidence . LWE-centric Constructions: A number of works are homing in on using primarily the Learning With Errors assumption, which is appealing due to its simplicity and resistance to quantum attacks . Brakerski et al. (2020), Wee and Wichs (2021), and others demonstrated iO constructions that, aside from a circular security assumption (considered a relatively minor leap of faith), rely solely on LWE. Circular security has been assumed in other contexts (like key-dependent message security) without issue, and might eventually be removable. These constructions are significant because if the remaining heuristic assumption is eliminated, we would have iO from just LWE achieving the holy grail of basing iO on a single core assumption . As of now, these almost standard schemes are still a bit heuristic but represent the cutting edge. Researchers are actively exploring ways to remove even the circular security assumption or replace it with standard hardness of a specific algebraic problem.

One interesting divergence in current research is whether to include LWE at all. The JLS approach uses LWE, but some follow-up work suggests that LWEs inherent noise might be a liability in obfuscation (because the noise in lattice-based encryption can leak information upon many uses). Indeed, Lin pointed out that the random noise that is crucial for LWE security tends to accumulate and could compromise obfuscations security if not handled carefully . The JLS paper managed this by combining with other tools, but Jain has hinted that subsequent efforts try to avoid LWE entirely to simplify constructions . This is somewhat ironic given the push to base iO on LWE; it underscores that the simplest assumption for general encryption might not be the simplest for obfuscation specifically. In any case, whether LWE is included or not, the fact remains that some structured hardness assumptions are needed, and current trends are trying to minimize and simplify those sets of assumptions.

5.2 Efficiency and Complexity Concerns

A glaring aspect of all known iO constructions is their astronomical inefficiency. The size of an obfuscated circuit and the time to produce or evaluate it are far beyond feasible. For example, earlier prototypes (using now-insecure techniques) were estimated to blow up a program of size 80 bits to more than 10 GB of obfuscated code, taking minutes to run . The more secure current proposals are even more complex Sahai remarked that the overhead is so high it is impractical to even estimate with precision . The complexity comes from many layers of reductions, encodings, and cryptographic primitives within primitives. Each step that makes the program more obfuscatable introduces a large multiplicative overhead.

The consensus is that efficiency, while a serious issue, is likely to improve with time. There is historical precedent: early constructions of multiparty secure computation or probabilistically checkable proofs were absurdly slow or large, yet decades of research brought them closer to practical viability, with improvements by many orders of magnitude . Barak draws an analogy to those cases, suggesting the current state of iO might be akin to the very first MPC protocol conceptually groundbreaking but ripe for optimization . Indeed, researchers are now looking at the myriad sub-components of iO constructions to see where optimizations or simplifications can be found. Every removed layer of complexity could potentially reduce that exponential overhead by a polynomial factor, which in aggregate could be huge.

5.3 Ongoing Research Directions

A few prominent directions in ongoing iO research include: Simplifying Assumptions: As mentioned, a drive exists to reduce the assumptions to a single core problem or at least a smaller set of well-understood problems. The motivation is partly aesthetic (a simpler foundation is easier to trust) and partly practical (every additional assumption is another potential point of failure). Work is ongoing to see if the coding assumption can be replaced by a variant of LWE, or if the pairing assumption can be dropped by using more lattice structure, etc. . The ideal endgame is iO based on a single assumption like LWE or on an assumption thats as established as (say) factoring or discrete log. Achieving that would likely remove much of the remaining skepticism in the community. Modularizing and Optimizing Constructions: Researchers are revisiting the current constructions to identify unnecessary steps. As Sahai noted, often you go back and realize you didnt need certain steps . There is a tightening mode now where the community is consolidating ideas different groups works are being compared and combined to eliminate redundancy. A more compact conceptual frame- work for iO is being sought, which would not only improve efficiency but also make security proofs easier to digest (right now verifying a full iO proof is an arduous task). The Simons Institute even hosted collaborative workshops where authors of various iO papers presented together to unify the perspective . Quantum Security: As quantum computing advances, its important to consider if iO remains secure against quantum adversaries. The inclusion of lattice assumptions like LWE is a positive in that regard (since LWE is believed quantum-safe). However, any scheme that uses classical number-theoretic assumptions (like elliptic curve pairings as in SXDH) would not be secure if large quantum computers arrive. Thus, one direction is to ensure iO can be based entirely on post-quantum assumptions. The LWE-centric approach is promising for that. If iO can be built from LWE (plus maybe a quantum-safe circular security assumption or a code assumption), then it would inherit post-quantum security. Some pieces like the Goldreich PRG (if used) also need to be examined for quantum resistance. Overall, aligning iO with the goals of post-quantum cryptography is on the roadmap. Applications and Synergies: While theory work continues, some researchers are exploring intermediate goals or specialized uses of iO-like primitives. For instance, domain-specific obfuscation (obfuscation for specific functions like simple algebraic functionalities) might be achievable with far less overhead, and could yield practical tools sooner. Also, iO has synergies with other emerging ideas like secure hardware enclaves (one could store an obfuscated program in an enclave for efficiency, etc.) and blockchain smart contracts (obfuscation could hide contract logic on a public ledger until conditions are met). The current research state includes investigating such hybrids using a bit of trusted hardware or a bit of multi-party computation to augment iO and reduce its burden.

In conclusion, the current state of iO research is one of cautious optimism and active refinement. We now have credible constructions that havent been broken, which is a big leap from a few years ago. The community is steadily chipping away at the complexity, trying to distill the essence of what makes program obfuscation possible. While we are still far from seeing iO in widespread practical use (or even a prototype for moderate-sized programs), the theoretical foundation is stronger than ever. Indistinguishability obfuscation is increasingly viewed as a real (if complex) object in cryptography, and ongoing research is firmly focused on making it simpler, faster, and based on unassailable assumptions.

6 Open Problems and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, indistinguishability obfuscation remains a young and challenging field. Many important questions are unresolved, and the path to practical, provably secure iO is still long. In this section, we outline several open problems and future research directions for iO .

| Open Problem | Current Status | Research Directions |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Im- provements |

Astronomical overhead; impractical for real use |

Optimize circuit components; ex- plore specialized hardware accelera- tion; restrict to important program classes |

| Assumption Mini- mization |

Multiple assumptions needed (LWE + coding + PRGs + pairings) |

Base iO on LWE alone; remove sub- exponential hardness requirements; find simpler assumptions |

| Practical Obfus- cation |

No implementations for non-trivial problems |

Develop domain-specific obfusca- tors; explore approximate obfusca- tion; create benchmarks |

| Post-Quantum Security |

Some constructions use quantum-vulnerable pairings |

Base iO entirely on quantum- resistant assumptions; study quan- tum obfuscation |

| Theoretical Im- plications |

Connections to com- plexity theory not fully explored |

Characterize complexity-theoretic consequences of iO; develop black- box separation results |

Table 2: Summary of major open problems in iO research.

- Improving Efficiency The most obvious gap between theory and practice is efficiency. Current obfuscation schemes are extraordinarily impractical, with size and runtime overheads that are infeasible for all but toy examples . A crucial open problem is to reduce the complexity of iO constructions by orders of magnitude. Achieving even a sub-exponential improvement (for example, bringing the overhead from exponential in the circuit size down to quasi-polynomial) would be a major breakthrough. Future work may explore new optimization techniques, perhaps by leveraging structure in the circuits being obfuscated (obfuscating restricted classes of programs more efficiently) or by discovering entirely new paradigms that avoid the costly steps of current approaches. As Barak noted, other areas of cryptography have seen radical efficiency improvements through sustained effort . A specific challenge is to streamline the chain of reductions in current iO proofs each reduction often blows up the size. If researchers can find a more direct way to go from assumptions to an obfuscation (fewer hybrid steps in proofs, fewer nested cryptographic primitives), this could cut down the overhead dramatically. Another angle is developing better heuristic optimizations in implementations (should anyone attempt to implement current iO); even though provable security might be lost, it could inform where the bottlenecks lie and guide theoretical improvements.

- Reducing Assumption Complexity While recent constructions have shed the completely ad-hoc assumptions, they still require multiple assumptions or strengthened forms (like sub-exponential hardness). A key open problem is to base iO on the simplest possible assumption(s). The ideal goal often stated is iO from only the Learning With Errors (LWE) assumption or something equivalently well-studied (perhaps factoring or discrete log, though those seem less likely given current knowledge). Achieving this would likely involve removing the need for certain components like the random oracle-like objects or specialized PRGs used in current schemes. It might also involve proving the security of some current heuristic (such as circular security) under a standard assumption, so it no longer counts as an extra assumption. Another intriguing possibility is basing iO on new complexity assumptions that could be more efficient or easier to work with than LWE. For example, the hardness of decoding random linear codes (used by JLS) might become a standalone assumption for iO if it gains enough credibility. Researchers are also exploring assumptions in idealized models (like obfuscation in random oracle model or generic group model) as stepping stones; while not real assumptions, these can highlight where we might eliminate or simplify things in the real world. In summary, assumption minimization is both a conceptual and practical pursuit fewer assumptions mean a conceptually cleaner foundation and often less complicated constructions.

- Foundations in Complexity Theory Indistinguishability obfuscation lies at an intersection of cryptography and computational complexity theory. Its existence (or non-existence) has implications for complexity separations. For instance, it is known that if iO for all circuits exists (with auxiliary input one-way functions), then certain complexity classes related to pseudorandomness and NP might have new relationships (there are results about iO implying NP is not in coAM or that certain proof systems exist under iO). A theoretical open question is to more precisely characterize the complexity-theoretic consequences of iO. Can we, for example, show that iO implies \(P \neq\) $N P$ (most suspect not directly, but iO does imply one-way functions which in turn imply \(N P \nsubseteq B P P\) so a world with iO is a world with secure crypto)? Conversely, could proving iO from weak assumptions inadvertently solve a major complexity question (for instance, basing iO on NP-hard problems would be surprising, since it might put those problems in a cryptographic context)? So far, iO has fit within our cryptographic world without shattering known complexity assumptions (e.g., it doesnt give \(N P \subseteq P /\) poly or such nonsense its consistent with known or believed separations). However, deepening the link between iO and complexity classes remains an open area. Another specific angle: is there a black-box separation showing iO cannot be based on certain classes of assumptions? Some works already show iO cannot be constructed in a black-box way from one-way permutations alone , suggesting needing richer structures. Mapping out these limits can guide which assumptions are worth targeting for iO.

- Cryptanalysis of New Assumptions With new assumptions (like the explicit linear code assumption, or certain structured PRG assumptions) introduced, another ongoing task is cryptanalysis attempting to break or weaken these assumptions, or finding the exact hardness boundary. The community needs to test the hardness of decoding the specific linear codes or the security of the specific PRGs used in iO frameworks. If weaknesses are found, iO constructions might need revision; if they hold firm, confidence grows. Unlike classical assumptions (RSA, AES, etc.), these new problems havent had decades of concerted attack efforts. So a future direction is to subject them to such efforts. This is not an open problem in the sense of something to construct or prove, but rather a crucial component of iOs maturation: withstand attempts of cryptanalysis over time. As Yael Kalai pointed out in a panel, confidence in assumptions grows over years Diffie-Hellman was once new and unproven, but now is standard. The same must happen for iOs assumptions. One could imagine future competitions or challenges set up to solve instances of the underlying problems (similar to RSA challenge), to gauge their security margins.

5. Toward Practical Obfuscation (Special Cases and Ap-

proximations) Achieving full iO for all circuits in a practical sense might be far off, but there are intermediate goals. One is obfuscation for specific function families that are particularly useful, under weaker assumptions. For example, can we obfuscate point functions (which are essentially digital lockers/password checks) efficiently? This is known to be possible under the existence of one-way functions (via simpler constructions like hashed password files), but doing it in the indistinguishability sense with full security has nuances. There are partial results (e.g., obfuscating point functions and conjunctions using specific assumptions). A related problem is approximate obfuscation:maybe we can live with an obfuscator that mostly preserves functionality (with small probability of error) if that circumvents impossibility for certain tasks. Barak et al. had extended impossibility to some forms of approximate obfuscation, but perhaps for restricted circuits, approximate obf. is viable. Another angle is measuring obfuscations efficacy: in practice, one might not need perfect indistinguishability, just enough that an adversarys job is sufficiently hard. This leads to considering heuristic obfuscators (like virtualization and software packing used in industry) and bridging them with theoretical iO to see if any security can be formally proven. While not exactly iO, this is a direction to gradually bring theory closer to practice.

- Obfuscation in New Domains The current definition of iO is for classical boolean circuits. Obfuscation for quantum circuits or protocols is an open frontier. Would an iO for quantum circuits even make sense (given quantum information can leak in new ways, and indistinguishability would have to allow quantum distinguishers)? Some initial work has started on defining quantum obfuscation, but its largely unexplored. If quantum computing becomes prevalent, understanding how (or if) iO can work in that realm will be important. Similarly, applying obfuscation to randomized functions or machine learning models is an emerging area. One can ask: can we obfuscate a neural network so that the model is hidden but it still produces the same classification outputs? This crosses into AI security and is partly practical, partly theoretical. The current iO theory mostly handles deterministic circuits; handling randomness (beyond what can be fixed by coin-fixing techniques) might require new ideas.

- Ethical and Security Implications Outside of pure research, a broader question looms: How will the availability of iO affect security overall? On one hand, it empowers defenders (e.g., protecting software, credentials). On the other hand, it could aid malware authors by making analysis of malicious code near-impossible. This dual-use concern isnt a problem to solve in the usual sense, but it is an issue that the community will eventually need to confront. Future research might consider obfuscation misuse detection (if that is even feasible) or build frameworks for lawful escrow if governments push back against widespread use of obfuscation. While these are more policy and ethical questions, they could influence technical designs (for example, perhaps future obfuscators have tracing capabilities combining watermarking to deter misuse).

In summary, the future of indistinguishability obfuscation research is rich with challenges. The field is poised between theory and practice: foundational questions about assumptions and efficiency are equally as important as exploring new applications and implications. A successful resolution of these open problems could eventually lead to a world where obfuscation is a standard tool in every security engineers toolkit providing a powerful way to secure software and cryptographic protocols. Reaching that point will likely require many incremental advances: shaving complexity factors, gaining confidence in assumptions year by year, and creatively adapting iO to new contexts. The journey of iO , often likened to a crypto dream, exemplifies the interplay of deep theory, system-building, and even philosophy of cryptographic design. The coming years will determine how this dream materializes into reality.

7 Conclusion

Indistinguishability obfuscation has rapidly evolved from a cryptographic curiosity into a central focal point of modern cryptographic research. In this survey, we explored how iO arose as a response to the impossibility of perfect black-box obfuscation, offering a weaker but achievable goal. We reviewed the formal definitions that underpin iO and traced the development of its theoretical foundations from the first heuristic constructions relying on novel algebraic assumptions, to recent schemes built on pillars of lattice, coding, and pairing-based cryptography. Along the way, we saw how iO has enabled a cascade of applications: long-standing problems like deniable encryption, functional encryption for general circuits, and advanced protocol tasks have seen solutions through the lens of iO , fundamentally changing the cryptographic landscape. We also discussed the current state of the art, noting that while no consensus standard model construction of iO is yet as simple as, say, RSA or AES, the community has made great strides in basing iO on assumptions we have reason to trust and in understanding the intricate web of reductions needed to make iO secure.

Several themes emerge from this exploration. First, iO serves as a powerful unifying framework disparate primitives and security notions can often be realized by constructing an appropriate program and obfuscating it, leveraging iOs guarantee to ensure security. This central hub quality of iO explains the tremendous excitement it has generated; it is no exaggeration to say that iO , if fully realized, would enable a form of cryptographic completeness, allowing us to bootstrap nearly any desired cryptographic functionality from basic components . Second, the path to realizing iO highlights the creative synthesis of techniques in cryptography: ideas from homomorphic encryption, multilinear maps, pseudorandom functions, and more all converge in service of obfuscation. The field has spurred new connections between cryptography and complexity theory, coding theory, and even software engineering principles. At the same time, our survey underlines a note of caution. Indistinguishability obfuscation today stands at a crossroads: constructions exist but remain enormously complex and inefficient. The assumptions, while more solid than before, need time and scrutiny to become universally accepted. There is much work left to be done before iO can transition from theory to practice. Open problems abound in improving efficiency, simplifying assumptions, and extending obfuscations reach. The coming years will be crucial for refining iOs foundations either reinforcing the confidence that it can be practical or identifying fundamental barriers that must be overcome.

In conclusion, indistinguishability obfuscation represents both a pinnacle of cryptographic ingenuity and a grand challenge. Its dual nature as an enabler of anything in crypto and a construct difficult to pin down makes it a fascinating subject of study. The progress made thus far gives reason for optimism: slowly but surely, researchers are demystifying iOs construction and strengthening its groundwork. If these trends continue, the once elusive goal of general-purpose program obfuscation may become a standard tool, profoundly impacting how we protect software and data. Even if hurdles remain, the journey toward iO has already enriched cryptographic science, leading to new techniques and deeper understanding. In the ongoing quest for secure computation and communications, indistinguishability obfuscation stands out as a testament to cryptographers willingness to tackle impossible problems and occasionally, to overcome them.

References

[ \(\left.\mathrm{BGI}^{+} 01\right]\) Boaz Barak, Oded Goldreich, Russell Impagliazzo, Steven Rudich, Amit Sahai, Salil P. Vadhan, and Ke Yang. On the (im)possibility of obfuscating programs. Electron. Colloquium Comput. Complex., TR01, 2001. (In pages 3, 6, and 7). [BV15] Nir Bitansky and Vinod Vaikuntanathan. Indistinguishability obfuscation from functional encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2015/163, 2015. (In page 4). [Edw21] Chris Edwards. Better security through obfuscation. Commun. ACM, 64(8):1315, July 2021. (In pages 3 and 5). [GGH12] Sanjam Garg, Craig Gentry, and Shai Halevi. Candidate multilinear maps from ideal lattices. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2012/610, 2012. (In page 4). [GGH \({ }^{+}\)13] Sanjam Garg, Craig Gentry, Shai Halevi, Mariana Raykova, Amit Sahai, and Brent Waters. Candidate indistinguishability obfuscation and functional encryption for all circuits. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2013/451, 2013. (In pages 3 and 4). [JLS20] Aayush Jain, Huijia Lin, and Amit Sahai. Indistinguishability obfuscation from well-founded assumptions. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2020/1003, 2020. (In page 5). [SW14] Amit Sahai and Brent Waters. How to use indistinguishability obfuscation: deniable encryption, and more. In Proceedings of the Forty-Sixth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, STOC '14, page 475484, New York, NY, USA, 2014. Association for Computing Machinery. (In page 4).

[^0]: \({ }^{1}\) New Developments in Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO) by Boaz Barak